Multifaceted relations with Beijing and revived ties with Russia are at the heart of the military junta's foreign policy

By Francesca Leva

Myanmar's foreign policy, deeply rooted in its struggle for independence, non-alignment, and neutrality, carries a rich historical significance. As a founding member of the Non-aligned Movement in 1961, the country played a pivotal role until it shifted towards the Eastern Bloc in 1979. The 2008 Constitution further solidified Myanmar's commitment to an “active, independent, and non-aligned foreign policy.” Even the decision to join the ASEAN in 1997, which marked a departure from its long-held neutrality, was a strategic move that effectively countered both China’s influence and Western countries’ pressure.

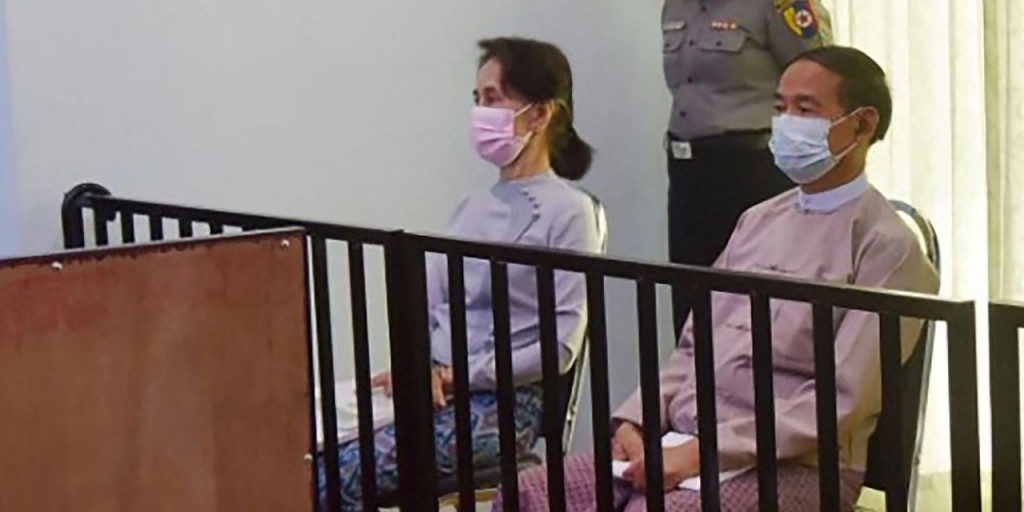

In 2020, Myanmar forged another strategic alliance with China, marked by the inauguration of the China - Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC), culminating in President Xi Jinping's visit to the Southeast Asian country. The CMEC vowed to be a strategic choice for both sides. For China, it was a means of gaining access to the Bay of Bengal and the Indian Ocean, transferring oil and gas via pipelines through Myanmar to Yunnan Province, providing new routes for transporting goods, and securing a source for importing raw materials. On the other hand, for Myanmar, the Corridor was necessary to break out of the economic stagnation of past years. However, the military coup of 2021 dramatically altered the balance. Before the military government, Naypyidaw could still rely on third-party actors to counterbalance Chinese expectations. In the aftermath of the coup, however, Myanmar found itself isolated, with collapsing foreign direct investment and a collapsing economy-these factors gave Beijing more leverage in the bilateral relationship.

China historically has deep relations with all components of Myanmar, from civilian to military. Not surprisingly, it had managed to broker a truce in 2023, but it was later interrupted by renewed fighting. Beijing's multifaceted interests in Myanmar contribute to its ambiguous foreign policy toward the country. On the one hand, Beijing has invested more than 35 billion U.S. dollars in local infrastructure projects and wants to prevent Western influence, hence its support for the military government. On the other hand, however, China’s security concerns are also at stake: there are 2.000 km of frontiers that the junta fails to control and that pose a threat to China’s infrastructure investments and are a vehicle to contraband, drugs, online scams, and people trafficking. China has thus turned to Myanmar’s ethnic militias to regain control.

As a result of these challenging dynamics, since 2022, there has been a noticeable diplomatic and economic convergence between Russia and Myanmar. Myanmar, strategically positioned, serves as a crucial access point to the Indian Ocean and the South China Sea maritime routes for Russia. In return, Russia acts as an ally to Naypyidaw, partially counterbalancing Beijing’s influence. The strategic importance of Myanmar to Russia is a key factor that underscores the geopolitical significance of the evolving alliances in the region. In May 2022, General Min Aung Hlaing visited Russia to expand the regime’s energy and defense cooperation with Moscow. Russia has since then supplied drones to Myanmar and has vetoed the UN Statements on Myanmar Conflict. At the International Economic Forum in Saint Petersburg in June 2023, the two countries signed deals on wind projects, established direct flights, and agreed to enhance tourism. Myanmar also purchased USD 1.5 billion in military hardware from Russia and discussed the possibility of setting up a tech center in Yangon with the perspective of the construction of a small-scale nuclear reactor.

Besides economic and military cooperation, there is an evident focus on energy joint projects between the two countries: since the military coup, Myanmar’s energy production has dropped by 47%, resulting in electricity shortages and power cuts throughout the country. This is mainly due to the fact that companies and foreign investors pulled out of the country because of the political situation. Due to the exchange rate, importing gas has become prohibitively expensive, forcing the military junta to rely on the existing hydropower plants, which are controlled by the EAOs – Ethnic Armed Organizations -. Ethnic Armed Organizations consist of different groups, each claiming ethnic recognition, and that have increasingly – although not unanimously – joined forces with the opposition National Unity Government (NUG) against the military junta.

The energy crisis in Myanmar, as well as its increasing international isolation, are forcing the country to forge new strategic alliances and find new partners to counterbalance China’s political and economic leverage, revitalize its economy, and find geopolitical support within the international arena.