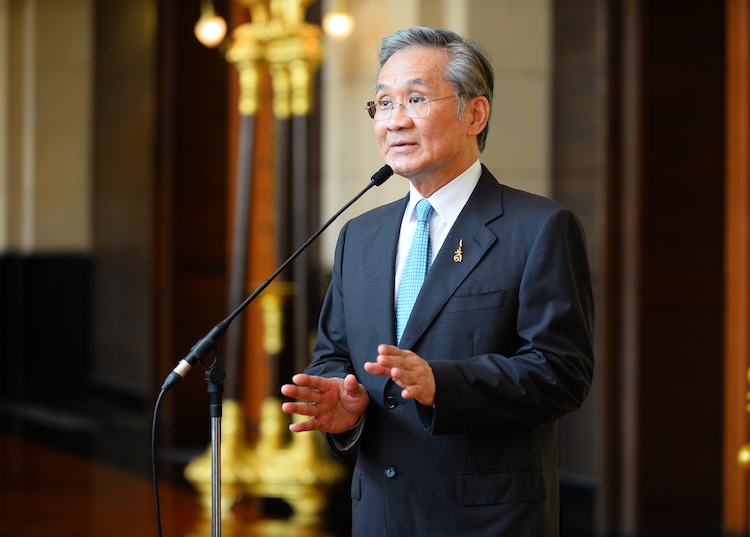

Multilateral diplomacy for sustainable growth in the era of disruption

Article by Don Pramudwinai, Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs of Thailand

The year 2020 was truly a disruptive time in world history. The fast-spreading Covid-19 pandemic managed to halt even the wave of globalisation and compelled governments to go into lockdown. Businesses were forced to close, in some cases leading to furloughs or unemployment, and further widening the existing social inequalities. Everyone came to the realisation that business would never again be the same, and began to accept the concept of a “new normal.”

The pandemic is a harsh reminder that our life is full of uncertainties and unknown parameters. In worst-case scenarios, we don’t even know what we don’t know, leaving us completely off guard once it happens. The damage from these ‘unknown unknowns’ or ‘black swans’, as called by some theorists, is increasingly troublesome since the world is getting smaller and more intertwined. In these conditions, for a medium-sized nation such as Thailand, we have always recognised that multilateralism, aiming for sustainable growth, will be the prevailing solution in response to black swans. The idea is that the challenges that hit us the hardest are usually the ones that undermine human security. Therefore, countries need to work in concert; otherwise, the problem will just linger, by perpetually shifting elsewhere. This has led to our advocacy of sustainable development in all the multilateral institutions we have either founded or joined, from the League of Nations to the United Nations, and regionally, from ASEAN to ACMECS and ACD, to name a few.

The rationale is evident and the benefits are foreseeable. Non-major powers have to combine capabilities to enhance political leverage or achieve shared goals that going solo will not succeed, such as climate change, sustainable development and, of course, pandemic management. COVID-19 has proven that traditional “great powers” have no power over such disruptions and need collaboration and networking to defeat this common foe. Recognising that “no one is safe until everyone is safe” underlines the significance of multilateral cooperation more than ever.

When the Cold War ended in the 1990s, economic cooperation became a prominent agenda, leading to the formation of regional groupings that Thailand joined or played an important part in founding. These include APEC, BIMSTEC, ACMECS and ACD. Together with ASEAN, these frameworks underpinned the notion of ‘prosper thy neighbour’ in Thai foreign policy and have brought about many tangible arrangements that have strengthened our resolve and solidarity whenever the region encountered ‘black swans’ in the past. The Asian financial crisis in 1997 and SARS in 2003 all presented us with valuable lessons.

The occurrence of COVID-19 and the way nations should coordinate their responses will presumably follow similar patterns in terms of regional cooperation. For instance, Thailand offered full support to Vietnam, the ASEAN Chair, in organising the Special ASEAN Summit and the Special ASEAN Plus Three Summit on COVID-19 in April 2020. We also proposed the establishment of the COVID-19 ASEAN Response Fund. This is reminiscent of Thailand’s hosting of the Special ASEAN and ASEAN-China Leaders Meeting and the APEC Health Ministerial Meeting when SARS hit the region in 2003. It rightly demonstrated the necessity and advantages of synergizing strengths to counter a common threat and prepare for any future disruptive challenges.

Throughout the years, Thailand has consistently pursued a common theme across all regional frameworks - the need to encourage sustainable growth that is balanced and remains grounded on basic human needs and rights. A common resolve on the part of the international community to not over-exploit resources will allow future generations to enjoy clean, decent and green social environments in any region across the world.

The post-COVID world requires a rethink – a paradigm shift – of how we pursue economic growth. Our current path has put human activities in direct conflict with nature, creating imbalances in the forms of climate change, the pandemic, and even social unrest. The Thai government recently made the Bio-Circular-Green Economy, or the BCG Model, our national agenda. It will be our main strategy for economic recovery and development after the pandemic and beyond. Through innovative and sustainable growth strategies that adequately meet human’s needs, helping lift millions out of poverty while respecting the planet, we hope to achieve a balance, or a middle path, that harmonizes production and consumption with preservation of the natural world. As other countries also share similar ideas, Thailand looks forward to working with like-minded partners to transform such concepts into concrete deliverables that will benefit people around the world at large.

As the current global economy is still struggling while Thailand’s main engines of growth show signs of slowing down, multilateral collaboration should be part of Thailand’s exit strategy. For example, to place Thailand in a better position in the global value chain, continued regional commitment to developing transportation networks and the harmonisation of regulations is essential. Meanwhile, the pandemic has spurred tremendous growth in digitisation in various areas, including business, telemedicine and remote education. We should take this opportunity to expedite cooperation to connect and upgrade our digital infrastructure and e-commerce.

Such trends align with the Thailand 4.0 strategy to transform the country’s economy into one that is technology and innovation-driven, with more valued-added industries. The Eastern Economic Corridor (EEC) lies at the core of this strategy and promotes investment in twelve targeted industries, such as next-generation automotive, smart electronics, and food for the future. All of these industries bode well for job creation and economic dynamism in Thailand and the region, as the EEC has become a notable magnet drawing foreign investors due to its logistical facilities and strategic location.

Thailand’s regional policy also advocates free and multilateral trade. It must be mentioned that the final signing of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) last year could not have been achieved without the expedition of negotiations over RCEP’s 20 chapters during Thailand’s Chairmanship of ASEAN in 2019, which was a huge feat. The agreement will widen trade and investment opportunities for Thai entrepreneurs to access a market of 2.2 billion people or nearly a third of the world population.

With such prospects, Thailand’s assumption of the chairmanships of the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral, Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC) from 2021 to 2022 and of APEC in 2022 is most timely. It places Thailand in a unique position to strengthen linkages and play a constructive role in designing a post-Covid economic recovery plan for regional growth that is sustainable and healthy.

Under BIMSTEC, Thailand will push for the improvement of land and sea links to strengthen transport infrastructure and facilitate trade. One of the flagship projects is the 1,360-kilometre trilateral highway from Tak Province, on Thailand’s western border, through Myanmar to the Indian border town of Moreh in Manipur State. With regard to maritime connectivity, Thailand plans to link Ranong Province on the Andaman coast to the port town of Krishnapatnam in India’s Andhra Pradesh, as an additional channel to promote inter-regional trade.

As far as APEC is concerned, Thailand intends to move the grouping forward and concretise the APEC Post-2020 Vision to promote trade and investment. We seek to promote digitalisation to boost economic growth, and improve business inclusivity for all groups of the population, particularly women, people with disabilities, and rural communities.

In this era of perpetual change, Thailand realises that both our inner strengths and international partnerships are vital if we are to be fully prepared for the “Next Normal” and be capable of harnessing external uncertainties. As the year 2021 is a transition phase towards post COVID-19 recovery, Thailand looks forward to working closely with our international partners in making a global rebound and shaping a sustainable future for our next generation.