By Sabrina Moles

From climate change to the economy, from human security to neighborly relations. Water management challenges bring the ten Southeast Asian countries closer together

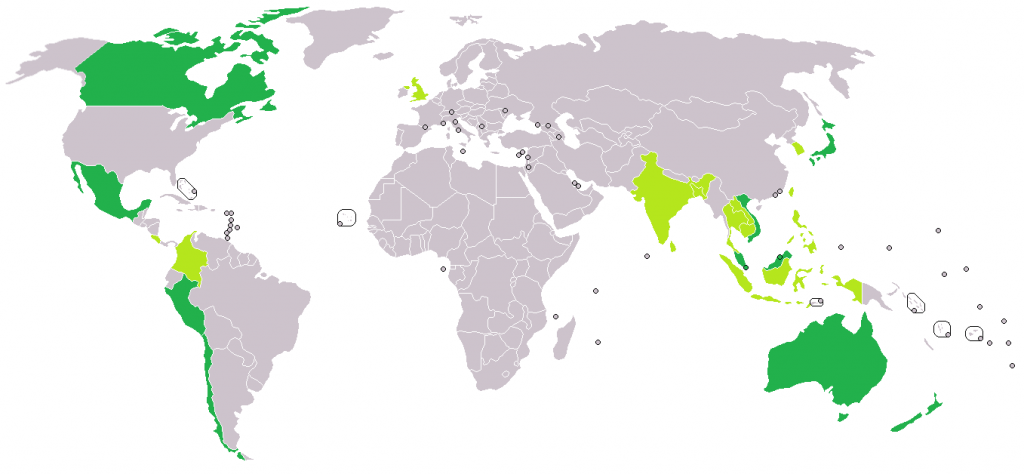

There is no life without water. Today, the management of water resources is one of the most delicate issues for Southeast Asian countries, where new and old challenges threaten an already very complex economic, political, and social environment. ASEAN is home to countries where the issue of water management is critical and threatened by climate change, while some member states have already developed the technical and logistical expertise to tackle water management challenges. This is precisely because water management affects a wide range of very different sectors, which are at the same time deeply interconnected and essential to development. Consequently, cooperation becomes one of the strengths of the group. But there is still a long way to go.

First, the pandemic has brought water security to the fore in terms of health, as underlined by the OECD report on management, access and safety of water sources. In 2012, the ASEAN Declaration on Human Rights explicitly guaranteed "the right to safe water and sanitation", but the 2021 budget shows that only a few member states include the right to water in their legislation and have been able to implement truly inclusive projects. In many areas of Southeast Asia, the provision of water services is inadequate and uneven, with unequal access between urban and rural areas. It is estimated that at least 1.7 billion people in Asia do not have access to basic sanitation, while in Southeast Asia alone, levels of contaminated water and unfit for human consumption are estimated to range between 68% and 84%.

Access to safe water resources is also a socio-economic problem, with the weakest sections of the population being penalized. Water privatization has, in some cases, contributed to poor coverage and high prices. An example is that of Indonesia where, since 1997, the British and French companies Thames Water and Suez have signed a 25-year public-private partnership contract for water supply of the capital city, Jakarta. Back then, only 42% of its residents had access to water at home, while many others still relied on bottled water or groundwater (also one of the main reasons why the city is sinking). The project promised that by 2017 it would reach 98% coverage but, in 2020, only 59.4% of the inhabitants could access clean water. This is not an exception. In most Southeast Asian countries, sanitation is underfunded and unevenly distributed, although access to safe water is on the rise in all ASEAN countries, with Cambodia (65%) and Laos (77% again). 5%) among the most penalized.

Another increasingly important element in a water resource management perspective is energy. For instance, the Mekong region offers enormous opportunities for the construction of dams and hydroelectric plants. Opportunities that have been seized mainly by Chinese investors. There are many multilateral mechanisms that have emerged over the years to discuss, study and implement projects around Mekong water management, as in the case of the Mekong River Commission (MRC). In this sense, Vietnam has emerged as a leading force inside these cooperation projects. Energy is understood as a potential push for development in a still very poor area. Indeed, the duties of the MRC include the drafting of ten-year or five-year plans on the various areas of use of the water resources present. According to the data, the energy demand downstream of the Mekong will grow at a rate of 6-7% per year: a trend that has stimulated the conversion of river water into hydroelectric energy, for a total of 89 completed projects and another 30 still in the planning phase.

The fact that the sources of the Mekong are in Chinese territory has often generated friction and provided the ASEAN countries with a reason for cohesion. Among the most controversial structures is the Jinghong Dam in the province of Yunnan, which alternately acts as a “tap” for the countries further south. The latest case dates to July, a particularly anomalous period for rainfall in China, when some "damages to the infrastructure" drastically reduced the water supply along the lower Mekong basin. Consequently, any intervention by Beijing on the waters of the Mekong can have a huge impact on the supply chain of the entire southern sector.

It is also a problem of climate instability. A challenge that exacerbates the impact of the flood and dry periods of Southeast Asian water basins and rivers Across the region, at least 34% of the population is frequently exposed to floods, while droughts have affected over 66 million people in the last 30 years. In a report produced by ASEAN and ESCAP (United Nations economic and social commission for Asia and the pacific), the trend is rapidly growing, with a significant increase by + 17%). Moreover, 4 out of 5 economic damages affect agriculture. From this it follows that the weakest sections of the population are among the most penalized, and are exposed to food insecurity caused by the destruction of crops. This is a very important factor, since the economy of the ten countries largely depends on the agricultural sector. As many as 61% of the labor force in Laos is employed in this sector, and remains stable at 47% in Vietnam, where a severe drought in 2016 led to the loss of more than 60% of revenue.

The management of water resources is therefore an essential factor in many areas: it follows that the problems related to the supply of safe and accessible water can become a conflict accelerator both at the domestic or regional level. It is estimated that 80% of conflicts in the world take place precisely in areas where the level of environmental degradation and the effects of climate change are more pronounced. All this also intersects with the risks associated with the loss of biodiversity.

With the worsening of extreme climatic phenomena and the reduction of water resources in the region, the ten ASEAN countries have begun to focus on regional cooperation to create resilient environments, economies, and supply systems. Among the solutions proposed by the group emerges the awareness that ex post intervention is no longer sufficient. In the intentions, priority should be given to prevention, such as monitoring climate trends and changes in the territory, to implement an alarm system before the phenomena turn into irreparable problems. This should lead to the creation of both technical intervention mechanisms and financial support for the categories most at risk, in particular small farmers and primary sector workers. Examples are the 2020-2025 Drought Management Strategy promoted by the MRC with the support of ASEAN and the United Nations.

The key to these risk absorption and prevention plans led to discussions on financial solutions capable of predicting the extent of damage and how to distribute aid. Among the objectives that emerge, the mitigation of climate change and universal access to water stand out as starting points for thinking about new plans for the management and exploitation of water resources at the regional level. The problem in this sense is not so much represented by the lack of funds (which are often part of aid packages promoted by international organizations), as by the careful management of the same to carry out projects capable of being first of all economically and structurally sustainable. in time.

Finally, the challenge will be to continue cooperating as a group on the delicate topic of water management, regarding the underdeveloped countries in the region, which in large part belong to the group. In this scenario, given the complexity of the sectors it involves, water management is threatened by new challenges. At the center of the debate will be the health crisis, the decline in GDP growth (down to a forecast of 4.3% for the second half of 2021 in ASEAN-5 compared to April of the same year), and the exacerbation of extreme climatic phenomena that are disrupting ecosystems.