The ASEAN giant chooses a different strategy to halt the advance of COVID and jumpstart the economy

The vaccination challenge, an extraordinary logistical enterprise made all the more daunting by manufacturing delays, requires tough choices. Over the past year, policymakers around the world have focused their efforts and resources first on research for vaccine development and then on the purchase of the doses needed to inoculate their fellow citizens. In recent months, however, a new question has taken center stage in the political debate: who will be given the first available doses?

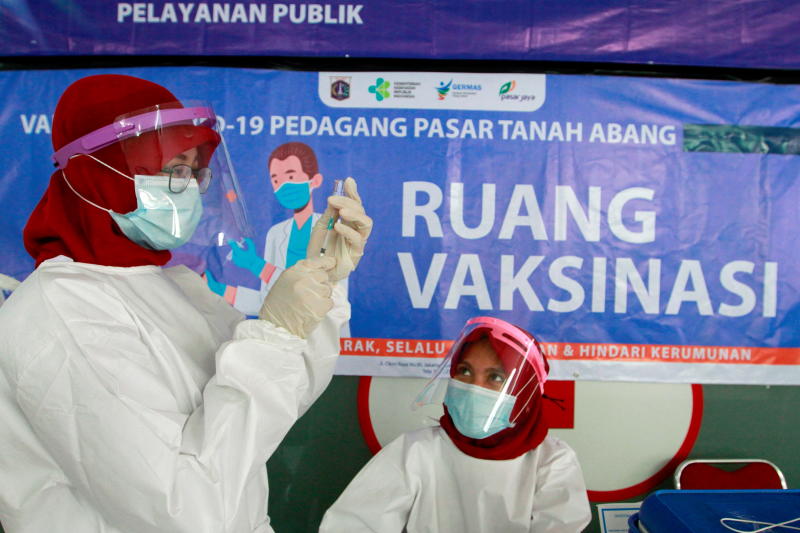

The discussion regarding the correct order of precedence in the administration of vaccines is of extreme importance. Once the vaccination of health workers has been completed, most of the EU Member States have chosen to give priority to the elderly citizens, considered the most fragile elements in the face of the virus, starting from the over-80s, the over-65s, and so on down. Indonesia, on the other hand, has chosen a different strategy: to vaccinate first citizens between 18 and 59 years old, the workforce, which represents more than 60% of the population.

The government chose to take this route for two main reasons. The first is purely health-related; Indonesian authorities hope to stop the advance of the infection by immunizing those who move around the most, whether for professional commitments or social activities. These people are more likely to be infected and consequently to infect others: 80% of COVID cases recorded in Indonesia are among the working population. The second reason is essentially economic; like and perhaps more than other world economies, in fact, Indonesia is paying a hefty bill for the epidemic. Recovery also means restarting tourism and transport, which are among the hardest hit sectors, and for this reason people need to be able to return to work as soon as possible, perhaps even to travel, in safety.

This result, according to Fithra Faisal Hastiadi, an economist at the University of Indonesia and spokesperson for the Ministry of Commerce, can only be achieved through a mass vaccination campaign of people of working age, starting, of course, with those who carry out a profession in which the risk of contagion is highest (health workers, the police and the military). Indonesia is therefore turning to the vaccine to solve both the health emergency and the economic crisis. In Hastiadi's words, "when we talk about public health we are also talking about economics, because public health is a function of economics."

Like all choices, this one too is not without its critics, and the Indonesian government has been accused on several occasions of not caring enough about the health of the weakest sectors of the population. However, Amin Soebandrio, director of the Eijkman Institute of Molecular Biology, defends Jakarta's strategy, stating that vaccinating workers first is the only way for Indonesia to achieve herd immunity and bring contagion under control. Another strong supporter of this choice is the Minister of Health, Budi Gunadi Sadikin, who, despite the fact that there are still no in-depth studies on the impact of vaccines on the spread of the virus, insisted that thanks to this strategy the elderly will no longer risk being infected by relatives who return home after a day in contact with other people.

Of course, when Indonesia started the vaccination campaign, it was not sure if it had enough doses to vaccinate the entire population, and the country only had the Sinovac Biotech vaccine, developed in China, which, at the time, was not considered scientifically effective and safe for the elderly. The approval for the use of Sinovac on the over 60s arrived on February 6th and in the meantime the government has reserved an additional 125 million doses of the Chinese vaccine and 330 million doses of AstraZeneca and Pfizer-BioNTech vaccines. Yet the government does not seem, at this time, intent on changing the order of priority in which the vaccine will be administered.

CB. Kusmaryanto, a member of the country's Bioethics Committee, says that in Indonesia it is not possible to "make good choices, but to choose the lesser evil." Indonesia's economy, the largest in Southeast Asia and tenth largest in the world on a purchasing power parity basis, overtook India in 2012 to become the second largest G20 member state in terms of GDP growth. Since the turn of the new century, Indonesia has cut poverty in half and prior to Covid-19 qualified for upper middle-income status. The government's plan now is to vaccinate 67% of individuals in the next 15 months, hoping that the strategy will prove effective and sufficient to put Indonesia back on its development trajectory.

By Carola Frattini